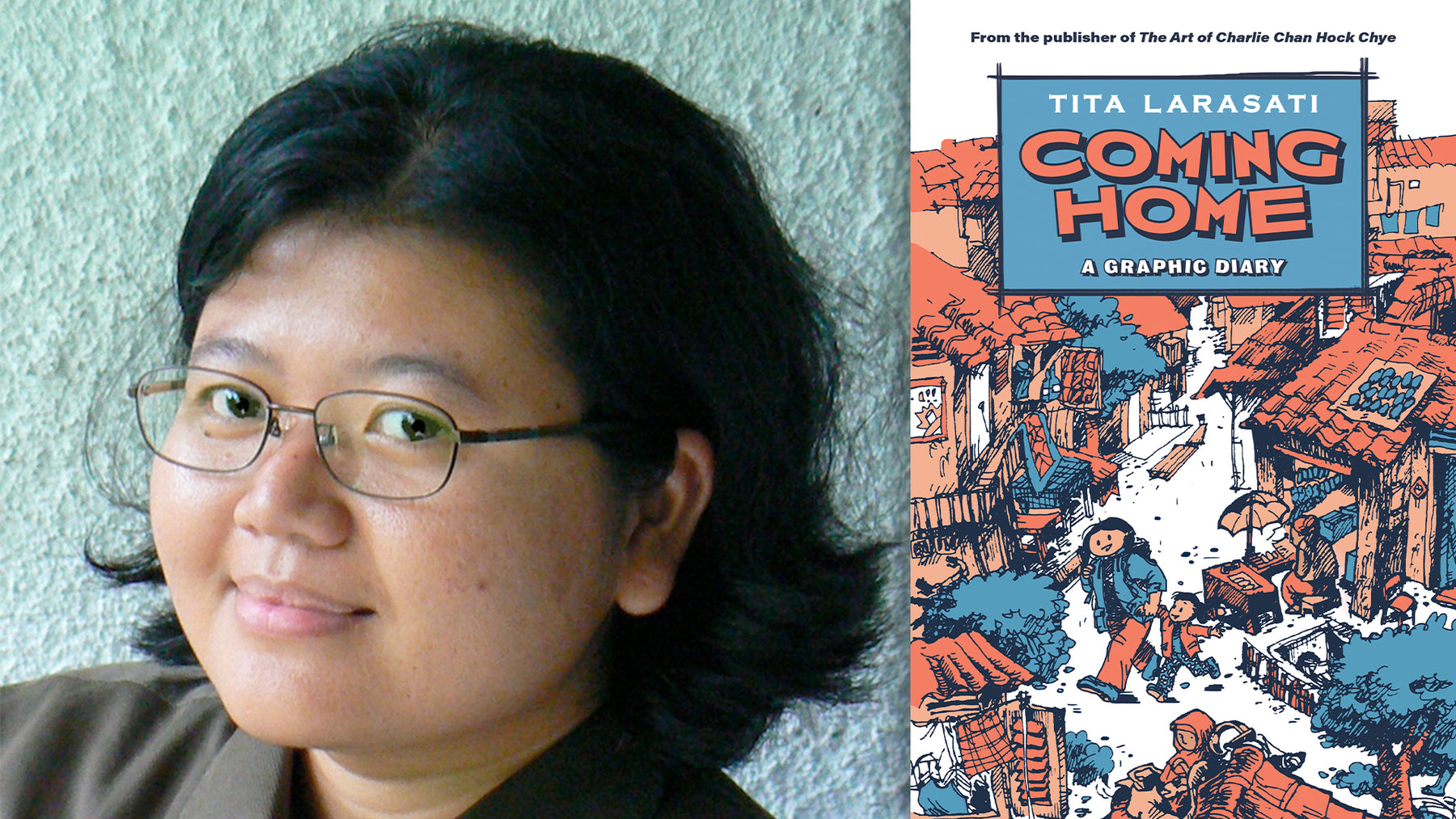

Doing the Write Thing: Tita Larasati

Tita Larasati is a lecturer and researcher at the Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB), and the author of Coming Home.

Tita Larasati is a lecturer and researcher at the Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB), and the author of Coming Home.

Born and raised in Jakarta, Indonesia, Tita left for Europe to further her studies. There, she began sending back letters to her family in the form of drawings. Little did she know that her mother loved them so much, she photocopied her works to distribute them to family and friends.

Tita decided to upload her drawing onto her blog to share her story with more readers. Needless to say, it was a huge success, and her works were compiled and published in the United States, the Netherlands, Brazil, and Japan. She then started her own publishing company, Curhat Anak Bangsa, in Bandung and published Coming Home as part of the series, Curhat Tita, pioneering a new genre of comics in Indonesia called "graphic diaries".

Now, as Coming Home arrives on Singapore's shores, Tita recounts her journey.

Why did you decide to make your book a graphic diary instead of a graphic novel or simply a memoir?

Because it is actually a diary, where I record daily occurrences, not only in writings but mostly in graphics. I didn’t start by an intention of creating a “novel”, since I know I wouldn’t have time for such ambition although I’d love to, one day. A “memoir” tends to mean that it is produced on purpose to make an autobiography, which also wasn’t my intention. I just want to record memorable, simple happenings around me—like a person taking a photograph of things she likes—and compile the results into an album.

How did your habit of recording and drawing daily happenings begin?

I actually never stop drawing since I knew how to use a crayon or a pencil. Whenever our family made a long trip, as far as I remember, we kids were each given a drawing book and a set of crayon or colourful markers. So when we’re bored, we were told to just draw. Or, whenever we went on a vacation, then my father (he’s an architect) used to make sketches too of the sceneries or objects around us, and I did the same while accompanying him. I haven’t really started compiling my drawings properly until 1995. I spent almost the whole year in Germany, doing my apprenticeship in a product design company. My German boss asked me to fax my parents every week, to send them news (about what I did in Germany). I thought, writing day-to-day happenings would be too tedious to read, so I fax them 1 page of drawings each week. (My mother used to make copies of my fax pages and distributed them to families and friends). By the end of my apprenticeship period, I ended up with about 100 pieces of A4 papers full of drawings. This habit apparently continues, even up to today.

Keeping a diary means you have to write and draw (if not, almost) every day. Do you ever suffer from writer’s block while journaling and how do you overcome it?

Keeping a diary means you have to write and draw (if not, almost) every day. Do you ever suffer from writer’s block while journaling and how do you overcome it?

I would like to be able to draw every day, but I don’t have as much time as I want. Opposite from a writer’s block, I have too many things in my head that I want to draw. Because I usually fill in my sketchbook in idle times (during a train trip, at a doctor’s waiting room, and so on), and if it so happens that I don’t have anything to ‘say’, I usually make sketches of my surroundings. To train my eyes and hands. So, the main challenge is actually finding enough time to do it, Other challenges, is when a book is about to get published, which usually relates to selecting the pages from my sketchbooks. My partner at Curhat Anak Bangsa, Rony, who is usually the one making the selection, remarked that he should pick the ones that can be easily understood even by an audience (or readers) who don’t know me in person.

When do you find time to work on your graphic diary, and what are your kids' responses when they see you draw them?

When I just started in 1995, I made them shortly before I went to sleep at night. During the period when I worked on my thesis, and then dissertation, I draw whenever I wanted to have an alternative pleasant activity, other than typing my research analysis and reports. Much later, when it has become more difficult to allocate a special “drawing time”, I draw whenever I can, usually to fill the time while waiting (for trains, for appointments, and such).

When they were much younger, the kids were not aware, of course, that they get ‘published’ (first on the internet, then on prints). Maybe it was only when they reached the age of 10 and 7 that they asked, “Why are you drawing us?”. I think I answered, more or less, the same as I wrote earlier, “Think of it as a photograph, but I capture the happenings in sequence, with pen on paper”. I think they just accepted the fact that a part of their lives is already exposed and put no further thought into it.

How did working on Coming Home help you in rediscovering Bandung and yourself?

Moving back to Bandung was quite a huge thing for me, since during my stay in The Netherlands, I rarely got back home to Indonesia. And if I did, there was hardly any time for me to explore Bandung and Jakarta (where most of my family members lived). So when I moved back for good, this time also bringing a family, it took a bit of getting used to. And since the adjustment was more of a challenge for my Dutch husband and our children, I hardly had any time to readjust myself, since I had to help them adjust first. So working on Coming Home served as a way for me to cope with our ‘new’ living environment. It helped to note down the changes from my viewpoints.

Which places would you absolutely bring a visitor to in Bandung?

The old part of the city: Braga Street and around. The street retains numerous Dutch-Indies colonial buildings, including Asia Africa Conference Museum, whose archives are included in UNESCO Memory of the World since 2015, Savoy Homann Hotel, one of the many iconic art deco buildings in Bandung. Then to the north, mountain part of Bandung, where art galleries are located. One of them is Selasar Art Space, whose premise includes also a cafe and a shop; while almost across it there’s Wot Batu, a stone park that belongs to the same proprietor.

Who are the graphic novelists, illustrators or writers who have inspired your drawing and writing style?

The answer would be difficult since I like to read many things. The first name that comes to mind is Eddie Campbell; I love his Fate of The Artist and his Alec series; and of course also his works with Alan Moore: From Hell and Birth Caul. My forever favourite is Lone Wolf & Cub by Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima, with its dynamic yet accurate graphics, next to its compelling storyline. Then there’s Marjane Satrapi with Persepolis and other works, all of which are thought-provoking. And of course, Lat—Kampung Boy feels like honest, from-the-bottom-of-heart stories. I’ll stop dropping names soon, but I should also mention Rutu Modan, whose style I wish I could adopt, and Neil Gaiman, whose stories always seem to lure to be visualised. My drawing/writing style has changed from one year another, and I think the style I have now is the one I’m most comfortable with. Since I draw directly with gel pen on paper (no pencil sketch prior to ink), I should choose a style that is most rapid and practical, that allows me to make ‘mistakes’ that actually add to the story.

You founded the publishing company, Curhat Anak Bangsa. Tell us more about how this came to be and what are your hopes and goals for it?

When I returned from The Netherlands, having my works published on the Internet and in prints abroad (in USA, Belgium, The Netherlands), I tried to have my works to be published in Indonesia. But no Indonesian publisher was interested at all. So Rony, whom I met at several comics events after my return to Bandung, offered a partnership to establish CAB. I agreed because we have a common goal: to provide an alternative style of Indonesian ‘comics’, to enrich the comics genres in Indonesia. We didn’t label it as “comics” since the term would make people expect stories that are "funny", or "romantic", or "heroic", as commonly found in comics at that moment; so we labelled it as “graphic diary”. This label also had the added purpose of directing people to the right bookshelf in a bookstore; it would not be displayed at “comics” or “children’s books” sections. When CAB started, in 2008, there was hardly any comic in Indonesia that depicts daily life, so the publication of Curhat Tita series was, in a way, an experiment. It turns out that those who read Curhat Tita are people who don’t usually read or buy comics, or those who can personify themselves with “Tita” (i.e. a parent of young children, or a working mother). In this sense, CAB succeeded to initiate a genre (biography-based comics) and to open a new target audience for Indonesian comics.

What kind of advice would you give to budding artists and writers out there?

Keep doing and improving what you like to do, and balance it so that you’ll never lose the joy of doing it.

How do you feel about your diary being read in different countries?

I think of it as having the stories distributed in a different form. Because, before being printed and available as books, the stories were already circulated in social media–by then it was mostly via Facebook and Multiply (that no longer exists). So I should be used to having a worldwide audience. I also think of it as works that should speak from themselves once they’re out there, and it’s quite pleasant to receive any kinds of remarks and reactions, even from people who don’t know me in person. It feels great.

How do you feel about Singaporeans being able to read Coming Home?

I’m really hoping to see more exchange of such works among our closest neighbours. Anthologies such as Liquid City3 and The Nanny (works from the 24 Hour Comics Day 2011 that includes a collaboration with a Singapore writer) are much awaited.